![]()

PHILIP GLASS

PHILIP GLASS

A Most Remarkable Encounter

The personal and musical friendship between Ravi Shankar and George Harrison has been known and well documented for decades now. It was a friendship that was powerful enough to make an impact on the large, musical life of the late nineteen sixties and it reverberates, as clearly, even today. I would go as far as to say that today there can scarcely be a musician or composer virtually anywhere in the world that is not aware of, nor been touched by, the fruits of the remarkable encounter between these two.

And what an encounter it was! Ravi Shankar, the older of the two, came with a complete command of the Indian musical tradition, both ancient and ageless. The other younger man, George Harrison, was a founding member of the Beatles; without question, the most influential and universally loved creators of today’s popular music. It was inevitable that this match would make waves, which it did on a tremendous scale and for a passionate worldwide audience.

Now, in fact these are recordings that have not been available for years. For some this will bring back memories of a past, rich and vivid enough to easily weather the vestiges of time. For many more it may be a first meeting with the music of two marvellous personalities. The magic of those years live again in these priceless recordings.

PHILIP GLASS

May 2010

![]()

INITIATION

INITIATION

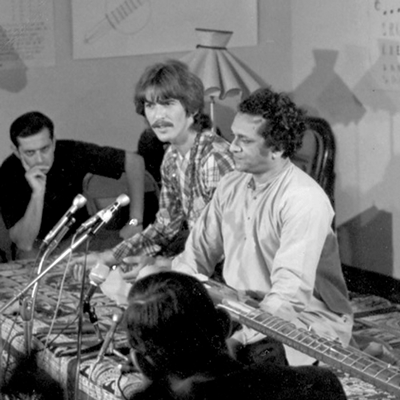

George and Ravi at a press conference, 1966.

Conversation

GEORGE: When I first consciously heard Indian music, it was as if I already knew it. When I was a child we had a crystal radio with long and short wave bands and so it’s possible I might have already heard some Indian classical music. There was something about it that was very familiar, but at the same time, intellectually, I didn’t know what was happening at all.

So I went and bought a sitar from a little shop at the top of Oxford Street called Indiacraft – it stocked little carvings and incense. It was a real crummy-quality one, actually, but I bought it and mucked about with it a bit.

"Norwegian Wood" was the first use of sitar on one of our records, though during the filming of “Help!” there were some Indian musicians in a restaurant scene and I first messed around with one then.

Towards the end of the year I kept hearing the name of Ravi Shankar. I heard it several times, and about the third time it was a friend of mine who said, ‘Have you heard this person Ravi Shankar? You may like the music.’ So I went out and bought a record and that was it: I thought it was incredible.

RAVI: He was already experimenting with his songs using the sitar, but he didn’t have proper training.

GEORGE: I listened to [Ravi’s records]…and although my intellect didn’t really know what was happening or didn’t know much about the music, just the pure sound of it and what it was playing, it just appealed to me so much. It hit a spot in me very deep and I just recognized it somehow. Along with that I just had a feeling that I was going to meet him. It was just one of those things.

![]()

MEETING

MEETING

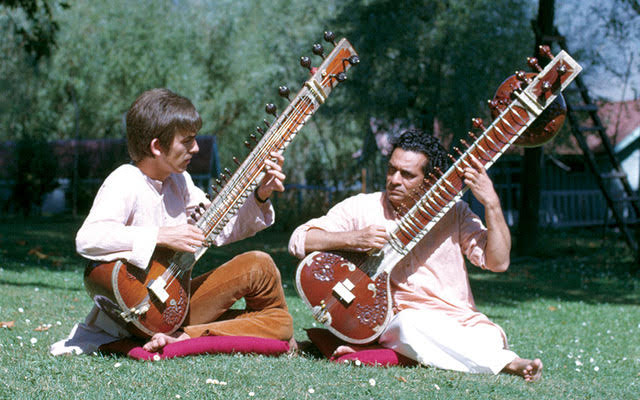

George and Ravi, 1965.

Ravi and George meet

GEORGE:...there was a society called Asian Music Circle. The fellow who ran that, who I’d got to know, he said, "Ravi’s going to come." He was in London, he was going to come for lunch and we met that way.

RAVI: The friendship with George started in 1966 and that’s when I met him along with the other three, but George was something very special from the very beginning. Something clicked between us and he was so interested in wanting to know about Indian music.

And he said he heard me, couple of times in the Royal Festival Hall at a concert, and someone came and tried to tell me that he had played sitar in "Norwegian Wood". And I felt bad again that I hadn’t heard about it (laughing). But anyway, that’s how it started and he, from the very first moment started asking questions, you know, in relation of spiritual feeling and music, and do I meditate, and things like that...the usual the young people are interested in.

GEORGE: I remember thinking I’d like to meet somebody who will really impress me. And that’s when I met Ravi, which was funny, because he’s this little fellow with an obscure instrument from our point of view, and yet it led me into such depths.

![]()

INDIA

INDIA

George Harrison and Ravi Shankar practice sitar. (© Harrison Family)

Conversation on India

GEORGE: Moustaches were part of the synchronicity and the collective consciousness. What happened to me was that Ravi Shankar wrote to me before I went out to Bombay, and in the letter said, ‘Try to disguise yourself – couldn’t you grow a moustache?’ I thought, ‘OK, I’ll grow a moustache. Not that it’s going to disguise me, but I’ve never had a moustache before, so I’ll grow it.’ So in September [1966], after touring and while John was making “How I Won The War,” I went to India for about six weeks. First I flew to Bombay and hung out there.

RAVI: So he passed through with a different name. So no one knew him. But in Bombay, Taj Hotel, one of the lift boys recognised him. And within minutes it was such a chaotic thing I tell you, because hundreds, and almost after two hours, thousands of boys and girls, young people, “we want George, we want George,” they were shouting… We knew that Bombay would be impossible, so we immediately booked our flight to Kashmir. And we went to Kashmir and stayed in a houseboat for about two weeks.

And along with that somehow I happened to give him a book Autobiography of A Yogi by Yogananda. And my elder brother Rajandra, he had also given him a book, by Vivekananda, so he was reading [all these] simultaneously and something was happening, it was like magic, with that whole atmosphere. Kashmir wasn’t like what it is today now, it was so peaceful ... being on a houseboat on the Daal Lake.

GEORGE: It was a fantastic time. I would go out and look at temples and go shopping. We travelled all over and eventually went up to Kashmir and stayed on a houseboat in the middle of the Himalayas. It was incredible.

RAVI: This is the time really we came to know each other much more, musically as well as, I would say philosophically. And then he very much wanted me to do something with a number of musicians, and I was also wanting to do the same thing… Though I was performing for 10 years prior to that and I was known very well and quite famous in the classical sense, you know, but meeting George…that created such a tremendous [interest] all over the world, especially among the young generation. And they immediately became interested in Indian sitar music and particularly me. Which helped me to become like a pop star almost, you know, a super star and all that. And that was because of George.

![]()

TERMINOLOGY

TERMINOLOGY

Guide to Indian Musical Terms

Alap

Introductory slow movement of raga calling forth its mood or rasa and dominant features. It is a pure musical presentation with no rhythmic accompaniment.

Apsara

Celestial nymph. Each raga is allotted an apsara and a well played raga is supposed to enhance the beauty of that nymph.

Badhat

An elaboration giving more fullness to the raga.

Bhajan

A Hindu hymn, from “bhaj”, meaning to partake of. A bhajan is devotional vocal music expressing bhakti – often sung in mixed ragas – sometimes group singing.

Bhakti

Ardent devotion to God.

Bhava

An emotion or deep expression which is experienced and projected by the musician.

Carnatic

Traditional South Indian musical style. Whereas the Hindustani tradition has allowed for more freedom and experimentation, the Carnatic music stays close to the roots. There is more emphasis on vocal music in the South.

Chaturanga

A four part form of traditional classical composition for voice which literally means “four limbs.”

Dadra

Light classical compositions with syncopated simple melodies.

Dhamar

a style of vocal music. The Krishna legends are the subject of this sensuous and romantic form of composition.

Gamak

A grace note which is an essential part of the performance of a raga.

Gat

A fixed composition appearing after the alap with the entrance of the tabla.

Gharana

A school or centre of musical culture which literally means “family tradition.” Gharanas flourished in North India under the patronage of Hindu rajas and Muslim nawabs. Usually a gharana is named for its place of origin (i.e., Indore Gharana) and each has distinctive characteristics in musical presentation.

Ghazal

A light classical romantic song (secular or devotional), which is derived from Persian Muslim sources. The lyrics are in Urdu (a language of Mideast origin, which uses Persian script, and is spoken by many Muslims throughout Pakistan and India).

Guru

A spiritual guide, master and teacher.

Gurumukhi vidya

A knowledge or art form learned directly from the guru.

Hindustani music

The North Indian style of music reflecting Islamic influence.

Jati

A cluster of notes from which a raga may be developed. It forms the skeleton of raga system.

Jhala

The climatic final movement of the raga. The melody notes are continuously interwoven with a pattern of drone notes.

Jor

The second movement of the alap which includes the addition of rhythm and combined weaving of melodic patterns.

Khyal

A prominent style of classical music, usually vocal, which literally means “imagination” or “fancy.” It has rich, delicately ornamented phrases, clear cut notes, and a theme usually from a love tale sung by a woman.

Krishna

The eighth incarnation of Vishnu (one of the three main gods of Hinduism) but also worshipped as an independent god. Although the word literally means “black,” Krishna is usually represented as the blue cowherd who plays the flute and charms the gopi maidens. He is celebrated in the Mahabharata, in which he espouses his doctrine in the section known as the Bhagavad Gita.

Matra

A unit of time in the system of tala or rhythmic patterns.

Meend

The act of sliding from one note to another. The sounds are connected by using shrutis or microtones.

Mela

The seventy-two parent scales on which ragas are based. It is an ancient arrangement of jatis with a stated ascent and descent of notes.

Nada Brahma

Sound is God. Nada is the omnipresent sound which may be perceived by those who are properly trained; Brahma is the omnipotent, absolute male manifestation of Brahman, the creative energy that motivates the universe. In Vedic music, it is believed that the power of music can influence human destiny and the order of the universe.

Prana

Life breath, divine energy. In Sanskrit there is no word for atheist because through the act of breathing one acknowledges this primary life force, in the air he imbibes without reflection.

Raga

The basic melody form defined by notes in a specific relationship to each other and upon which the musician improvises. A specific raga may be associated with a time of day or year, a particular emotion or divinity.

Rasa

Juice, sap essence or pith. When applied to music it is the emotion, the flavour evoked by the raga.

Sadhana

Dedication in the complete spiritual sense of losing one’s identity through a single-minded concentration. Literally sadhana means “gaining.”

Samavadi

The second most important note of the raga, usually the fourth or fifth.

Saraswati

The goddess of knowledge usually represented as holding a veena.

Shiva

One of the three major gods of the Hindu triad. He is the great aesthetic and destroyer who danced the world into existence.

Taan

Phrase based on vowel, syllables or words extended by expressive passages which may be sung or played in any tempo.

Tala

A rhythmic cycle, the essential element of musical time.

Tappa

A vocal style originating from the rural music sung by Punjabi Muslim camel drivers. A continuous melody, greatly ornamented with strong rhythm and fast tempo, recounts a Punjabi love tragedy.

Tarana

Fast moving song style using as text nonsense syllables or the mnemonic syllables used for drumming.

Tarang

Literally it means a “wave” of sound and is achieved by a circle of instruments tuned at a cumulative, ascending pitch based on the raga being performed.

Thumri

A vocal and instrumental form, the most free of all classical styles. Its melodies are lyric and romantic. Lines or words are repeated in varied rhythms. Ragas, folk, and popular songs may be included in one composition.

Ustad

A title of respect for any notable, highly-learned man.

Vadi

The most important note of a raga.

Vedic

Pertaining to the Vedas, books of the orthodox Hindus revealed by the Godhead. Vedic music is the oldest surviving form of Indian music (intoned mantras for ritual offerings and sacrifice).

![]()

INSTRUMENTS

INSTRUMENTS

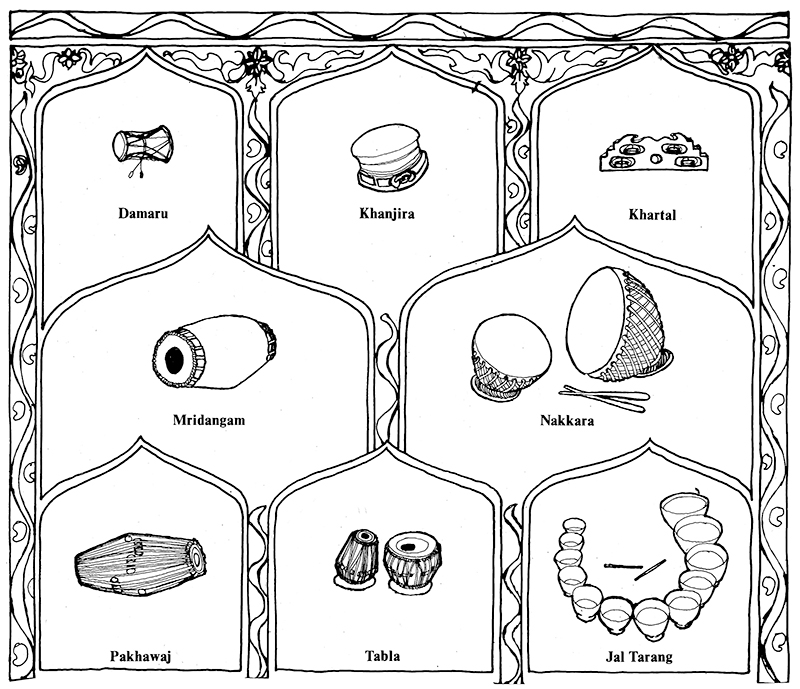

Stringed | Wind | Percussion

Indian Musical Instruments

By Naseem Khan

As well as presenting different musical disciplines, this Festival also serves as a demonstration of Indian instruments. Many varieties will be performed upon, from the simplest village drum to the most sophisticated classical instruments with hundreds of years of tradition and discovery behind them.

The aim is a panoramic view of Indian music - an insight into the richness of a tradition that began in the villages and reached its apogee in the princely courts.

The world of Indian music is constantly shifting - as it must to retain creative vitality. Some of the instruments to be heard tonight, for instance, were recently considered limited folk instruments. But due to the dedication and talents of specific masters, their wider potential has been recognized; the most striking examples are the santoor and the shahnai. The array of instruments presented tonight demonstrates the progress possible from folk to classical status and sets each instrument in a total musical context.

STRINGED INSTRUMENTS

STRINGED INSTRUMENTS

Ektara

ek, one-tar, string. There are many regional variations to this instrument, which is found most often as a rhythmic accompaniment to devotional songs among wandering musicians and religious mendicants. The instrument illustrated attenuates the pitch of the string by tension applied to the flexible bamboo strips. The bowl at the base may be made of wood, gourd or metal.

Santoor

This delicate Kashmiri instrument until recently was found more often in museums or in use in rural areas for playing the simplest folk music. It has an august past, particularly in Persia, where it still flourishes. The Sanskrit name for the santoor is Shata Tantri Veenathe - the hundred string veena. On the modern santoor more than a hundred strings run across a hollow rectangular box. They are paired and each set has a bridge. The strings are struck by a pair of slim, carved, walnut mallots.

Sarangi

The name derives from sau rangi - a hundred colours - a reference to the elusive, shimmering beauty of this instrument. Four main strings are bowed and as many as forty resonate below. Originally the sarangi was used to accompany vocal music, but due to the genius of great masters such as Ustad Bundu Khan, it is a respected solo instrument in the concert halls of today.

Sarod

Sarod type instruments have been found in carvings of the first century in the Champa Temple and in paintings in the Ajanta Caves. The instrument was modified by Amir Khusru in the eleventh century, but the definitive changes were made by Ustad Allauddin Khan near the turn of the 20th century. The hollow body is carved from a single piece of well seasoned teak wood and the belly is covered with goat skin. The musician uses his fingernails for the meend ornamentations to slide on the unfretted metal fingerboard. There are four main strings, six rhythm and drone strings and fifteen sympathetic strings, all made of metal. The main strings are struck with a plectrum made of coconut shell.

Sitar

The sitar, now the best known Indian instrument in the West, has a long and complex heritage: it’s origins go back to the ancient veena. In the 13th century Amir Khusru, in order to make the instrument more flexible, reversed the order of the strings and made the frets movable. He renamed the instrument seh tar, three strings. It has a long teak body with a hollow gourd at the base. The metal strings are played with a plectrum worn on the right index finger. The average sitar has four strings for playing, two or three drone and rhythm strings and eleven to thirteen resonating strings under the frets.

Swaramandal

This small hand-held harp has strings made of coiled wire which are tuned by individual pegs or screws. It is similar in appearance to an autoharp or zither and is played as a drone or supporting instrument by brushing the fingers over all the strings. Occasionally individual strings are plucked to play a melody or emphasize important notes of a raga.

Tanpura (Tambura, or Tanboura)

The inevitable tanpura is the hypnotic drone heard in every classical music performance. The long necked instrument has no frets and the four to six strings are stroked by first, the middle finger and then the index finger - from left to right. The tanpura usually has three strings tuned to the tonic, or sa, of the raga being performed. The neck is of wood and the rounded base may be either of wood or gourd.

Vichitra veena

This comparatively recent addition to the veena family is a fretless string instrument with four main strings, three drone and rhythm strings, and eleven to thirteen resonating sympathetic strings. The main strings are stopped by a piece of solid glass about the size and shape of an egg, which is held in the left hand. The strings are plucked by plectrum worn on the index and middle finger of the right hand. The hollow body of wood is supported by two detachable gourds.

Violin

The violin was introduced into India about three hundred years ago by the Portuguese and quickly became popular, particularly in the South, where it remains the most important bowed instrument today. The instrument is not held in the Western style, but played in a sitting position fixed between the right foot and the left shoulder, thus allowing greater freedom of the hand in executing the different ornamentations.

WIND INSTRUMENTS

WIND INSTRUMENTS

Flute

Simple bamboo flutes, traditionally associated with the god Krishna are found in every part of India. Every possible size exists - from enormous bass flutes to small treble ones. They all have simple holes rather than keys and may be played vertically or in the transverse position.

Shahnai

The shahnai is a double reed instrument, varieties of which are found in all parts of the world. Its closest relative in the West is the oboe. It is a particularly auspicious instrument in India. No marriage, birth, or move to a new house is complete without the sounds of the shahnai. In the South of India, a larger version, the Nadaswaram is used. Embedded though it is in ceremonial occasion, the shahnai has the flexibility to develop its own classical tradition.

PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS

PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS

Drums are to be found in various forms throughout India. They range from the simplest aboriginal holes in the earth covered with skin to complex sets that need meticulous tuning and have a very sophisticated tradition. While the flute is associated with the god Krishna, the drum is connected with the god Shiva. The damaru was shaken by him as he danced the universe into existence.

Damaru

The damaru is an hour-glass shaped drum with regional variations in size and details of construction. Vellum heads, tied to hoops on both sides are tightened by ropes. The damaru is struck only on one side by either the hand or a stick. The ropes are pressed and released in rapid succession, varying the tension on the heads and thereby changing the pitch.

Dholak

The dholak is a popular folk drum throughout Northern India. The barrel shaped wooden frame has parchment heads held by hoops and laced over the body by cotton cords. The left head of the drum is generally weighted with paste made of iron filings. The paste is applied to the inside of the left head in order to decrease the tension and lower the pitch. Additional tuning is accomplished by the use of small metal or wooden rings which slide along the cords attached to the head. This varies the tension and the pitch may be raised or lowered.

Khanjira

The nearest Western equivalent to this instrument is the tambourine. Like the tambourine, it consists of a circle of skin stretched on a wooden frame. In North India the skin is usually goat, while in the South it is lizard. The wooden rim of the khanjira is held in the left hand which also applies pressure to the surface to create pitch variation. It is struck with the fingers and palm of the right hand. The duff is similar to the khanjira but much larger, sometimes having a diameter of three feet. It is played either with flat sticks or with the hand.

Khartal

Khartal are wooden clappers with jingles made of thin brass plates inserted into the wooden body. They are played with one hand and held between the thumb and four fingers.

Khol

The khol is a Bengali folk instrument traditionally used as an accompaniment to devotional chants in Bengal. The instrument has a clay body and two skin surfaces. To give the clay body strength, the entire body is laced with leather straps. The right hand surface gives a sharp, high pitched sound while the left gives a hint of bass. Regional varieties of the khol exist. In Manipur a similar drum, the pung, is used to accompany the classical dance. The pung has a body of wood.

Madal

The madal is an impressive sounding tribal drum with a lower pitch than the khol. It’s popular among the Santhal tribesmen of Bihar and Bengal. It is a long clay drum; the right surface is bass, the left even deeper. The Santhals use thirty to forty madals in unison to produce a pounding, heavy sound.

Manjira

Manjira are small brass symbols that traditionally form an essential background for devotional songs. During this Festival however they are used purely for their individual sound quality.

Mridangam

The mridangam is to the South what the pakhawaj and tabla are to the North, the premier classical drum. It resembles the former but the heads have a different texture and the paste for the bass surface varies. The sound is more metallic, less heavy, than the pakhawaj.

Nagara

The nagara is an enormous kettledrum usually found in temples. It has a history of ceremonial usage. It was housed in a high place usually at the entrances to palaces and forts where, with the shahnai, its sonorous tones announced the happenings of the day. It was also hung from the backs of elephants and sounded as a war drum. At times it is used to accompany folk dances such as the Chau dance from Bengal. The drum is pounded with two sticks.

Nakkara

The nakkara is of the same family as the nagara; in fact, many ethnomusicologists believe that regional variations in pronunciation are the real differences. They are the same shape, but the nakkara is played in pairs. The left hand drum is the bass and the right hand, smaller drum, is the treble. They also are used for ceremonial occasions and to accompany the shahnai.

Nal

The nal is a long bodied wooden drum - a cross between the dholak and pakhawaj. It is very popular in Maharashtra where it is a vital part of religious ceremony as well as of local dance-dramas. Pitch is controlled by the thick strands of cotton rope that run the length of the drum, from face to face.

Pakhawaj

The pakhawaj, a long-bodied wooden drum with both ends covered in skin, is the most traditional drum of North India. It is commonly used as an accompaniment for the Dhrupad and Dhamar styles of singing. Played horizontally, with the fingers and palms of both hands, the right-hand surface is tuned with a hammer to the pitch required. The left-hand surface is anointed with a paste made from wheat flour (atta) and provides the bass sound. The combined result is a deep rolling sound that carries suggestions of the regal dignity of elephants.

Tabla

Some four hundred years ago, the pakhawaj underwent a process of binary fusion. The result was two smaller drums of which the right hand is the tabla and the left the bayan or bass. The overall term for the two is Tabla. The tabla is tuned with a hammer. The black disc in the centre of the right-hand drum is rubbed with a mixture of ground rice-flour, coal and iron dust; the same mixture is used on the bayan. With the change from Pakhawaj came a change in technique. Instead of striking the surface with an open palm, the musician uses the base of the palm as well as the fingers on the bayan, to produce a variation in sound. The tabla has come to be used commonly as an accompaniment for the Khyal and Thumri styles of singing that developed from the Dhrupad style, and also with music and dance.The word tarang means “wave” in Sanskrit. Groups of instruments which are tuned sequentially produce a wave of sound.

Duggi tarang

The Duggi Tarang was virtually created by Uday Shankar and has since grown in popularity. Like the Nakkara, it consists of one bass drum and one treble. This drum is tuned by screws. They are played with sticks, and have a duller more sonorous sound than the Tabla.

Jal tarang

The Jal Tarang is essentially a water-xylophone. It is made up of a series of china bowls of varying sizes. They are carefully filled with varying levels of water, in order to achieve the musical range required. They are played with two light sticks.

Duff

A folk drum used in various parts of North India. Consists of a piece of skin stretched over an octagonal or round wooden frame, of variable sizes, on one side only.

Kash tarang

The Kash Tarang is somewhat like the Western xylophone, but is made of wood rather than metal. It uses the chromatic scale with half notes, and is struck by two wooden sticks.

Tabla tarang

The Tabla Tarang is a collection of Tablas, each tuned to a different pitch. Together they cover about one and a half octaves.

Tasha

The Tasha is a very high-pitched kettledrum made of wood and skin. It is struck by two flat sticks.